The Saw Kill is a tributary of the Hudson River, making the stream and the area of land around it part of the Hudson River watershed. Because the Saw Kill joins the river at the South Tivoli Bays, the mouth of the stream is affected by tidal activity. As an estuary, the Hudson River is tidal with two low tides and two high tides a day. It also has currents, and therefore, runs in both directions depending on the time of day and the tides. This inspired a Native American name for the river, Mahicannituck, the river that flows two ways. The Hudson has an influence of salt water; today, the salt front ends much further south near Newburgh. Prior to the modern construction of dams along the river, the tide reached far beyond Cohoes and even to Amissohaendiek, Fish Creek, and beyond. The Hudson River begins in Lake Tear of the Clouds on Mount Marcy in the Adirondacks and runs three-hundred-fifteen miles until it connects to the Atlantic Ocean. From NYC to Troy, around one hundred fifty-three miles, the river is considered an estuary.

The Saw Kill watershed is an area comprising 26.2 square miles, from its rocky headwaters in Milan through the rich farmlands of Red Hook and the silt and clay at the mouth near Bard College. The watershed has a long history of human occupation. Some archaeological evidence suggests human habitation from as early as 12,000 years ago, when glacial landscapes were actively carving and depositing the geological features we see today. These earliest people are believed to have been nomadic hunting groups, following now extinct megafauna.

Archaeologists have dated sites around Tivoli Bay as old as 7,000 years BP (before present). Evidence from these sites shows that earlier inhabitants were smaller family units, who followed seasonal rounds to procure resources throughout the year. Oral traditions, along with archaeological and linguistic evidence, point to the arrival of Algonquian-speaking people in the Hudson Valley area from points west, thousands of years ago. These people kept close relations with their kin, the Lenape (who white settlers called the Delaware). The people who settled in this area called themselves the Muh-he-con-neok, the People of the Waters That Are Never Still, which we now know as the Mohicans. As groups slowly and gradually began to rely more on cultivated food resources, settlements grew and became more permanent. The Woodland Period, as this time is called, began around 2700 BP. Evidence shows that the floodplains in what is now the Tivoli area were planted with corn, squash, beans, sunflowers, and other crops that could be stored and traded. Significant archaeological evidence shows long, continuous use of migratory fish resources along the mouth and falls of the Metambesem (the Saw Kill) and the large river that flows both ways, Mahicannituck(the Hudson). Sturgeon plates and mussel shells are some of the most ubiquitous materials found at riverine Mohican sites.

The Saw Kill, known as Metambesem by the indigenous people of the area, may have referred to the rapidity of the water that flows through it (See Ruttenber, 1906).

One early land record of the Metambesem comes in a British deed of land from the Colonial Governor of New York, Thomas Dongan, to Colonel Pieter Schuyler, who in 1688 apparently “purchased” the land from the “Indians”:

“…on the east side of Hudson’s river in Duchess county, over against Magdalene Island, beginning at a certain creek called Metambesem; thence running easterly to the south-most part of a meadow called Tauqushqueick…”

Deed as quoted in Smith, et al, 1882 p. 38

The Dutch and English settlers changed the name from Metambesem, to the Saw Kill, which more or less is equivalent to “(saw) mill creek”. The areas surrounding the mouth of the Saw Kill were shaped by the activities of the settlers and their slaves, who tilled and cleared the land, built roads, dams, and mills, in the nascent nation. It is important to note, that prior to their arrival, the Mohicans and their neighbors had a long history of shaping the landscape, through fire, agriculture, and the creation of natural fences to encourage easier hunting.

Historic Landowners of the Region

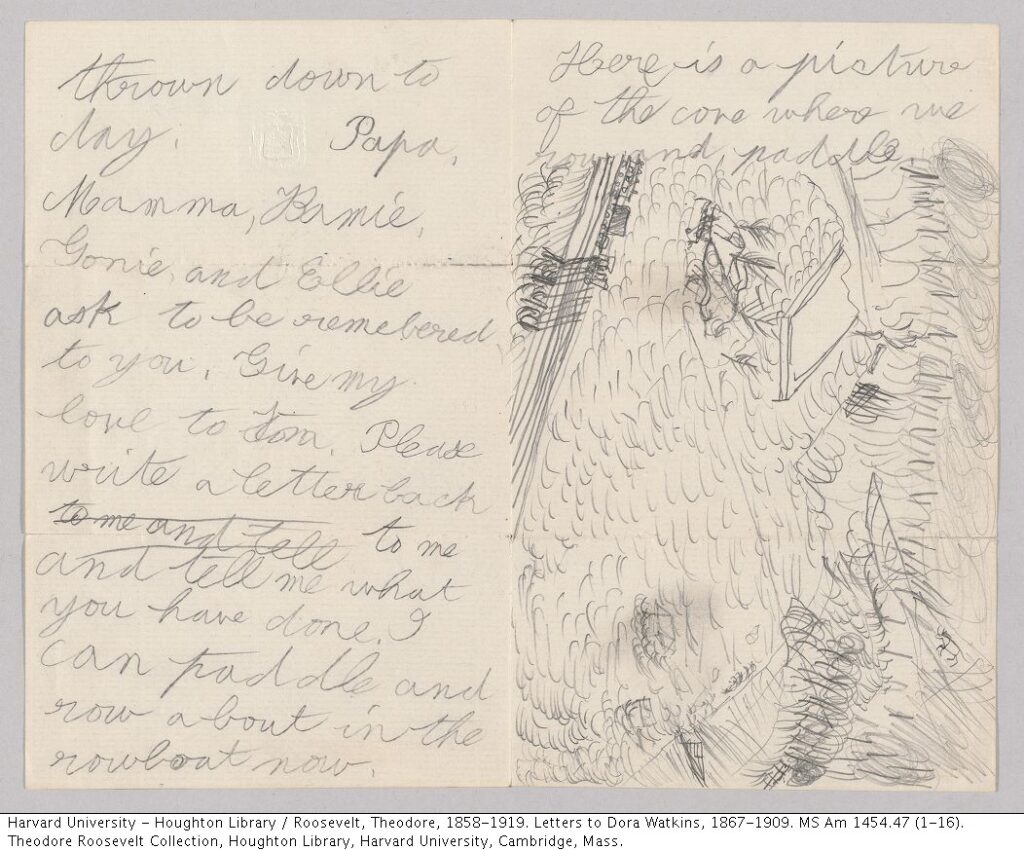

Montgomery Place was the home of Janet Livingston Montgomery, built in 1802. Janet purchased the 242 acres that would later become the famous Montgomery estate for $3,300. Montgomery Place remained the home of the Livingston family until 1985, when it was sold to Historic Hudson Valley. As prominent society members in the region, the Montgomery family had many relations and visitors, including ties to Presidents Teddy Roosevelt and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Teddy spent a formative summer in his youth at Montgomery Place. See his hand-written letters and drawings of rowing on South Tivoli Bay and animals he observed here.

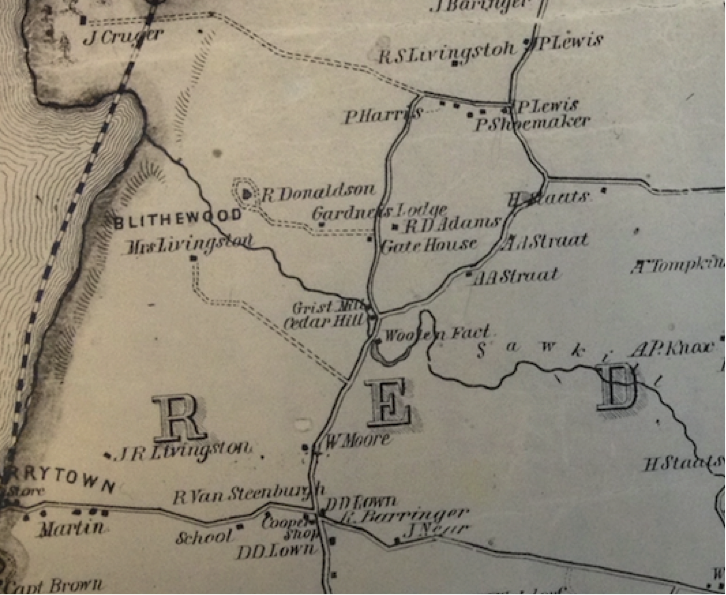

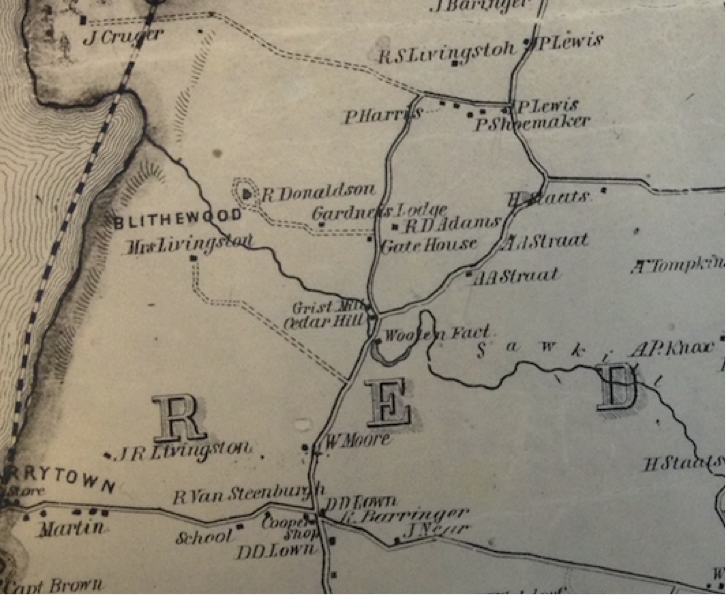

Robert Donaldson, owner of Blithewood, started building his estate in 1835 with architect Alexander Jackson Davis and landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing. It was Donaldson’s idea, in 1841, to buy the land on either side of the Saw Kill with Louise Davezac Livingston of Montgomery Place in order to prevent further industrial development next to their properties.

Rokeby, or La Bergerie, is an estate in Barrytown built by John and Alida Livingston Armstrong from 1811 to 1815. It was bought in 1836 by William Astor, husband of Margaret Livingston, and remains the home of Astor and Livingston descendants to this day.

A History of Arts

The Hudson Valley was the home of many well known artists, notably Frederic Church of The Hudson River School of painters and owner of Olana. However, not all artwork of the Hudson Valley centered around the Hudson River. The Saw Kill was featured in prints and paintings by Jacques-Gerard Milbert (1766-1840) and Alexander Jackson Davis (1803-1892) during the 19th century.

A History of Conservation on the Saw Kill

“And it is further agreed that covenants shall be inserted in the conveyance and all subsequent conveyances that the Saw Kill and the water power shall not at any time hereafter be used for milling or manufacturing purposes…”

Letter from Garret Van Keuren (lawyer) to Louise Davezac Livingston, February 5th, 1841, MP.2005.669, Historic Hudson Valley, Pocantico Hills, NY.

Those who have either visited or lived in the Hudson Valley know of the area’s serene, natural beauty. It was the beauty of the Saw Kill, specifically, that inspired the making of one of the earliest conservation covenants in the United States. The quotation above, from their correspondence about the making of such a covenant, shows their mutual commitment to protecting the Saw Kill. Formed between Louise Davezac Livingston of Montgomery Place and Robert Donaldson, the owner of Blithewood, their legal agreement prevented the development of mills and other factories along the Saw Kill in order to protect the natural beauty of the landscape.

The actions of Robert Donaldson and Louise Livingston reflected the sentiment of many wealthy landowners at the time. As industrialism flourished throughout the United States, development in the Hudson Valley pushed landowners to secure the sanctity of their homes by buying more of the surrounding property. Nevertheless, the Saw Kill as we know it today would probably be much more degraded were it not for their efforts. In addition to agriculture, wineries, and orchards, the logging, brick making, and milling industries had a very significant presence in this region.

Continuing Conservation in the Hudson Valley

The conservation covenant formed to protect the Saw Kill in 1841 is not the only historic act of conservation in this region. Over a century later, factory development would once again become a pressing issue in the Hudson Valley. Storm King Mountain was set to be destroyed by Con Edison’s proposed hydroelectric power plant, but thanks to the actions of six Hudson Valley residents that would later become the founding members of Scenic Hudson, the beauty and ecology of Storm King and the Hudson River was protected. Scenic Hudson’s 17 year long legal battle with Con Edison (from 1963 to 1980) was unprecedented in the United States and led the way to our modern day grass-roots environmental movement.

40+ Years of Water Quality Sampling

In May of 2016, SKWC and the Bard Water Lab (now the Bard Community Science Lab) re-started water quality monitoring begun 40 years ago in 1976. Two of the members of the original team of community scientists — Sue Ellis and Sheryl Griffith — were back in 2016 to test for physical, chemical, and biological indicators of water quality on the Saw Kill.