Each Spring, several species of amphibians (salamanders, frogs, and toads) emerge from their winter hibernation to migrate back to the vernal pools where they were born to lay their eggs for the next generation. Some of these amphibians travel great distances, crossing roads to get to their final destination. To help them migrate safely, the NYSDEC started the Amphibian Migrations and Road Crossings Project (AM&RC) over 10 years ago to train volunteers to help with the road crossings and also collect important data about the conditions of the migrations nights, which species are observed, and how many (alive or dead) are spotted at various locations. The Saw Kill Watershed Community works in tandem with the Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) to collect and share data and observations within our watershed. In addition to sending the data to the DEC, the SKWC also uses the data to help assess the health of the watershed and to identify future local conservation efforts.

Become an Amphibian Migration Volunteer!

If you are interested in joining the SKWC/Red Hook team in future years, please complete this brief Google Form:

Volunteers are expected to view the DEC AM&RC Volunteer Training series on YouTube prior to the spring migration, which can be anytime between mid-February to mid-April, though typically happen during the month of March. By volunteering with the SKWC team, you are committing to share your data with both the SKWC and the DEC.

HELPFUL LINKS:

- Red Hook Salamander Facebook Group — join and follow for updated information posted there.

- Overview of the AM&RC Project

- AM&RC Fact Sheet

- Volunteer Handbook — data sheets can be found on pages 10-11 in the volunteer handbook.

- Amphibian Identification Chart

- Volunteer Training Videos on YouTube:

SAFETY SUPPLIES

To support safety on migration nights, we have some limited supplies available on a first request/first served basis to lend out. Let us know if you need anything and we can arrange a pick-up/drop-off:

- Reflective safety vests

- Reflective road signs

- Flashlights

- Laminated amphibian ID charts

- Guidebooks

- Factsheets

Overview of the 2021 Amphibian Migrations in Red Hook, NY

Over 3 rainy nights in March, we had over 60 volunteers help move over 700 amphibians to safely reach their breeding pools. Species included yellow spotted salamanders, Jefferson/blue-spotted salamanders, four-toed salamanders, redback salamanders, eastern newts, wood frogs, spring peepers, American toads, pickerel frogs, green frogs, grey tree frogs, and several bullfrogs.

In early spring, on rainy nights when the temperature is above 40° F, salamanders and frogs emerge from hibernation in woodlands and migrate to breeding pools in small wetlands to mate and lay their eggs. Because these migration routes often cross roads at night, these small amphibians need our help to keep out of harm’s way.

Here in Red Hook, 2021 was an exciting year for amphibian migrations. The Saw Kill Watershed Community, under the leadership of our amphibian migration coordinator Amy Shein, put out the call in late February for volunteers to help with the DEC Amphibian Migrations & Road Crossings Project (AM&RC). The project tracks amphibian migration in the Hudson Valley and reports the data to the DEC for analysis, helps amphibians cross roads safely, and scouts out new migration crossing points.

Our local volunteers came through! In March, we had three fairly big migration nights. The first was on March 18th, with temperatures hovering around 41° F and dipping down to 39° F. Undeterred by the weather, our volunteers dressed warmly and headed out in rain and mist to a variety of known and suspected migration sites. They found the first amphibian species to emerge: yellow-spotted salamanders, a Jefferson/blue-spotted salamander (a NYS Species of Special Concern), a few four-toed salamanders (NYS Species of Greatest Conservation Need), and lots of wood frogs and spring peepers. The next migration night was March 24th, much warmer at 52° F. This was the biggest night of the migration season. In addition to the species observed the previous week, volunteers also reported red-backed salamanders, eastern newts, American toads, pickerel frogs, green frogs, and gray tree frogs. Our final night, March 28th (51° F), saw more of the same, with the addition of several bullfrogs.

Of note, four barred owls were spotted by volunteers on migration nights, including one that took off with a spotted salamander in its mouth! The migration nights must also be big nights for those creatures who depend on these small amphibians for food in our local forest ecosystem.

All in all, we had over 60 volunteers head out on one or more of these cold and rainy spring nights to help approximately 700 amphibians migrate safely across the roads to breeding pools nearby. We were able to confirm some suspected crossing locations, added some new crossings, and will use the data to identify potential sites for future migrations. This information will identify key areas that would benefit from additional protection, especially the areas used by rare species.

These species, their breeding pools, and the surrounding woodlands are important features of the Saw Kill watershed. In addition to serving as important habitat, these wetlands improve water quality, store water, and mitigate flooding. The presence of rare species is an indicator of high-quality habitat.

The Saw Kill Watershed Community looks forward to gathering additional information for this project in the coming years. See you next spring as our project continues!

Read the Imby article on 2021’s Migrations!

Salamanders and Frogs: Where Are Their Busiest Road Crossings?

By Karen Schneller-McDonald

Over the past few months, we’ve reported on the progress of our annual Amphibian Migration Project. As we wrap up this year’s project, we want to again thank all of the volunteers who ventured out to count migrating frogs and salamanders and move them out of harm’s way. The information collected by our volunteers was sent to DEC and we also retain it for our records. We’ll use this information to plan next year’s project, predict where crossings are most likely to take place, and identify key amphibian habitat so it can be protected. Key species tend to return to the same breeding pools year after year.

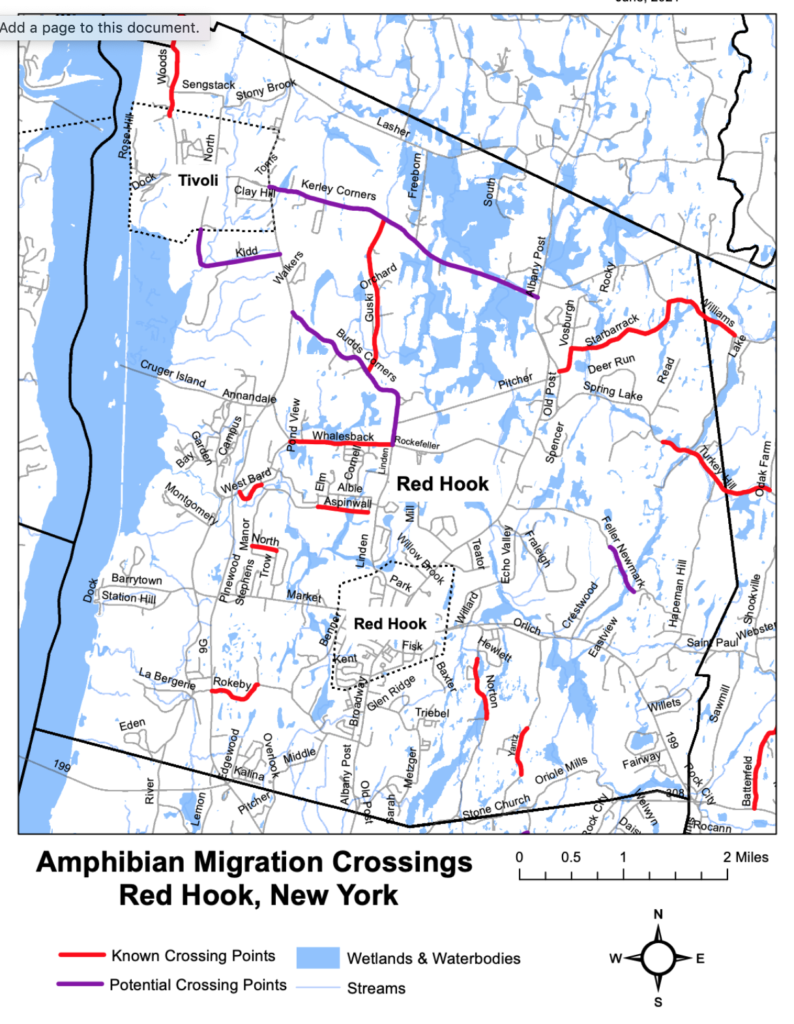

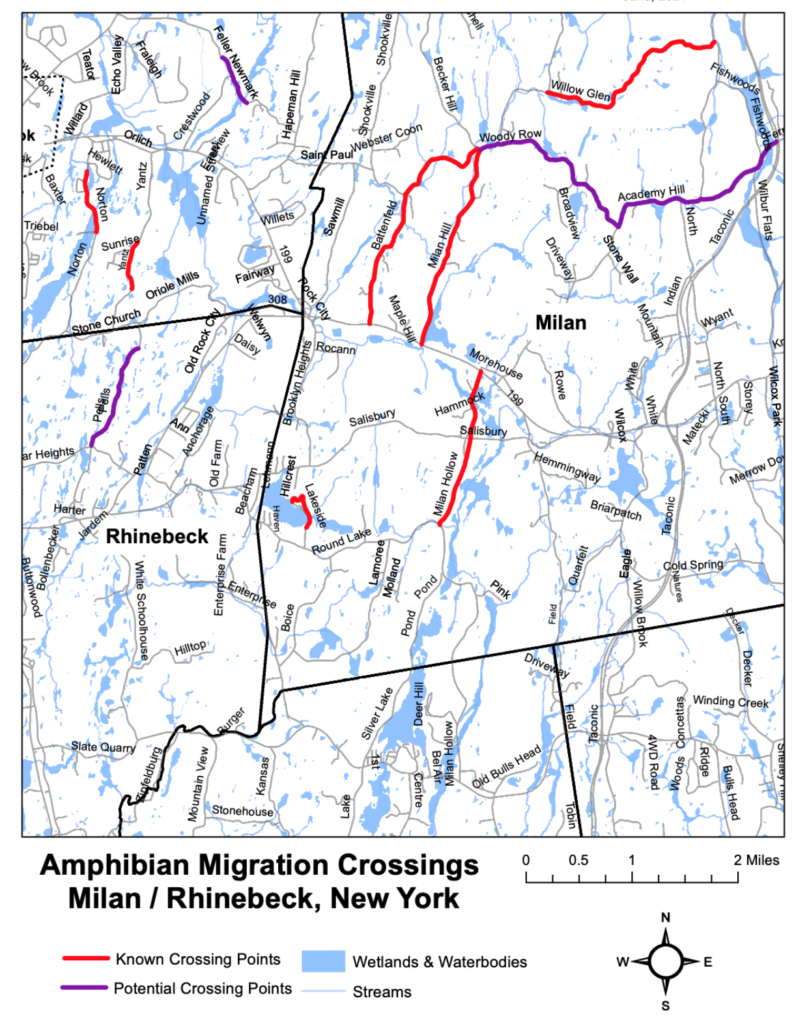

This year volunteers identified five species of salamanders, six frogs, and one toad species. Our new crossing maps show twenty sites that are known crossings, and seven potential crossing sites. Some of these crossings were notable for species diversity, sheer numbers of individuals, and species of special concern, as described in the following sample of information from this year’s migration season (late March).

SPECIES DIVERSITY AND NUMBERS

Half of the known crossing sites had at least four amphibian species. Seven to ten species were identified at six sites (Norton, Whalesback, Rokeby, Battenfeld, Woods and Starbarrak/Williams). Wood frogs and spring peepers were by far the most numerous species found, with more than 300 individuals of each reported throughout the area. The iconic spotted salamander pictured on our tee shirts was most numerous at five sites: Milan Hollow Road, Norton, Whalesback, Rokeby, and Round Lake.

SPECIES OF CONCERN

We found two species of salamanders of conservation concern: the Jefferson/blue spotted salamander, NYS listed species of Special Concern and Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) High Priority, and the four-toed salamander, listed as SGCN-High Priority, which the DEC defines as “The status of these species is known and conservation action is needed in the next ten years. These species are experiencing a population decline, or have identified threats that may put them in jeopardy, and are in need of timely management intervention or they are likely to reach critical population levels in New York.” Hybridization occurs between blue-spotted salamander and Jefferson salamander. Because of the difficulty in identifying these hybrids without genetic testing, this salamander is broadly referred to as the Jefferson/blue-spotted salamander complex.

A total of five Jefferson/blue-spotted salamander complex individuals were found at only three crossings (Woods Road, Norton, and Round Lake Road). These are very low numbers, and we’ll be looking for more data in future. For comparison, we found 120 spotted salamanders, a closely related species, at 14 crossings.

Preferred habitat for this species is deciduous forest and mixed deciduous-coniferous forests with abundant stumps and logs, bottomland forests adjacent to disturbed and agricultural lands, and open areas, including pastures and grassy fields that support permanent or ephemeral pools or ponds. Breeding occurs in ephemeral pools and wetlands adjacent to woodland habitats, typically with forested shoreline and emergent vegetation. Fish-free ponds are preferred, but some populations will breed where fish are present. This salamander can migrate as far as 2,000 feet to reach breeding pools. Major threats include road crossings and habitat loss due to land development.

Four-toed salamander occurrence is patchy throughout NY State. These small salamanders are often difficult to find, though they may be locally abundant in a few areas. This appears to be true for several sites in our watershed. We recorded a surprisingly high number of individuals, 175. Most of them were found at three crossings (of the seven crossings where they were identified), at Woods Road, Norton, and Starbarrack. Habitat is moist forests with adjacent wetlands that contain sphagnum hummocks or moss hanging over open water, a vital component for nesting. Such areas include bogs, swamps, fens, wet meadows, vernal pools, and the edges of lakes and ponds–typically wetlands with a forested canopy and some input from groundwater, seeps, or small streams.

NEXT STEPS

SKWC will correlate amphibian crossing data with land use, terrestrial habitat, and likely breeding habitat in wetlands (depicted on our watershed map). We’ll visit known and

potential crossings and new sites next year so we can build on this year’s information and continue to identify most important crossings and associated breeding pools. In addition to the sites used by our two species of greatest concern, other sites are significant for the number of individuals and variety of species they support.

When this information is combined with water quality data and tributary and headwaters information, we can more accurately identify significant habitats that support sensitive species. Our goal is to determine how these areas–and their resident amphibians-can be protected.